Microstructured hydrogels can be used as drug delivery systems for the treatment of Hepatitis C.

© xrender/iStock/Thinkstock

An improved design of hydrogel implants for sustained drug delivery has been developed by A*STAR researchers and successfully tested in a mouse model as a treatment for hepatitis C.

Hydrogels are cross-linked polymer networks that absorb water or biological fluids. Due to their compatibility with living tissues and ability to preserve embedded proteins in their natural state, they are a good vehicle for delivering protein drugs into the body. A significant problem, however, is the early and uncontrolled release of the embedded proteins.

“We have found a way to regulate the rate and duration of drug release,” says Motoichi Kurisawa of the A*STAR Institute of Bioengineering and Nanotechnology (IBN), who worked with researchers from the A*STAR Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology.

The IBN team created hydrogels based on a complex carbohydrate called dextran. Their key breakthrough is the use of polymer polyethylene glycol to incorporate micrometer-sized domains within the gel. These domains act as reservoirs for a protein drug when the drug molecules are also linked to polyethylene glycol. The chemical interactions between the modified protein and the reservoir domains allow a slow and steady release of the protein, a considerable improvement on existing alternatives.

By tweaking the dimensions of the microstructures in the gel, the researchers could also control the rate at which the drug is released, which further increases the system’s flexibility. Another advantage is that the non-toxic hydrogels degrade naturally after releasing their cargo.

Tests on the hydrogels bathed in surrounding fluid demonstrated sustained release of the protein interferon over three months, which is much longer than less sophisticated hydrogels can achieve.

The real test, of course, is performance in a living system. Kurisawa and his colleagues demonstrated their technology as a potential way to treat hepatitis C. This serious liver disease kills around 500,000 people each year worldwide, but damage can be limited by interferon. Existing treatment requires eight weekly injections in hospital, which is time-consuming, painful and causes side-effects including depression and fatigue.

The new interferon-loaded hydrogel was implanted in mice — that serve as a model of hepatitis C in humans — and the results were encouraging. “This single administration prevented liver disease as effectively as the current procedure of repeated injections,” says Kurisawa.The next stage will be clinical trials in humans.

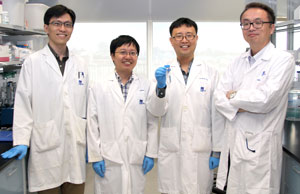

The IBN researchers who developed the new drug-delivering hydrogel for the treatment of hepatitis C. From right: Motoichi Kurisawa, Ki Hyun Bae, Keming Xu and Fan Lee.

© 2015 A*STAR Institute of Bioengineering and Nanotechnology

Kurisawa says the team is seeking a suitable healthcare partner to bring the technology to market. He also points out that the system could in principle be applied to deliver many other drugs.

The A*STAR-affiliated researchers contributing to this research are from the Institute of Bioengineering and Nanotechnology and the Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology. For more information about the team’s research, please visit the IBN Nanomedicine group webpage.