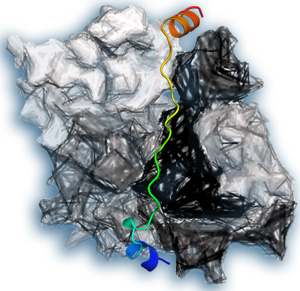

An illustration of thymosin-β4 (colored) bound to actin (gray).

© 2015 A*STAR Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology

Insight into the regulation of cell skeleton structure has come from a study conducted by A*STAR researchers. The work, which solved a protein structure that has eluded scientists for 20 years, should lead to further insights into many cellular processes and could even help to combat cancer.

The outer membrane of a cell is supported by a cytoskeleton that is built from actin, a globular protein that links together to make chains, which in turn form fibers that make up the skeleton. Lengthening and shortening of actin chains enables rapid changes in the cytoskeleton, a crucial adaptive process.

“Actin is essential in numerous cellular processes, including cell motility, cell division, cell signaling, establishment of cell junctions, and maintenance of cell shape,” explains lead author Bo Xue from the A*STAR Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology. “In addition, cancer cells often become invasive by increasing migratory signals to the cytoskeleton.”

A pool of unlinked actin is stored in cells to enable immediate changes to the cytoskeleton, but this pool requires tight regulation to prevent actin chains forming randomly. Two proteins involved in this regulation are thymosin-β4 (Tβ4) and profilin. The structure of profilin has been known for 20 years, but since then attempts to solve the structure of Tβ4 have failed. Xue and colleagues succeeded by fusing actin and Tβ4 so as to image the structure when the two proteins were bound together (see image).

The team saw two different structures of Tβ4, each bound differently to actin. One structure concealed the chain-forming regions of actin, explaining how Tβ4 blocks chain formation. The other allowed profilin to bind to actin at the same time. In this complex, Tβ4 and profilin each modulated the strength of the other’s interactions with actin.

“When combined with biochemical assays and molecular dynamics simulations, such details allow us to propose a mechanism of actin exchange between profilin and Tβ4, the two major players in maintaining the monomeric actin pool,” explains Xue.

The researchers suggest that the two proteins can pass actin between them without allowing it to freely move inside the cell, preventing it from adding to the cytoskeleton in a random way.

“This general mechanism of actin regulation is applicable to many cellular processes in cells that contain β-thymosins and profilins,” explains Xue, who says that such insights could have more specific applications. “A deeper understanding of actin regulation will enable researchers to find better ways to fight cancer,” he concludes.

The A*STAR-affiliated researchers contributing to this research are from the Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology.