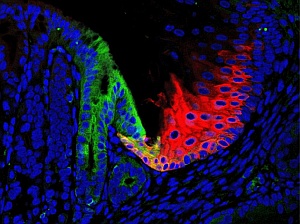

Residual embryonic cells (green) in the adult mouse give rise to Barrett’s-like metaplasia, and may be prevented from spreading by guardian cells (red).

Barrett’s esophagus is a medical condition in which the lining of the esophagus is damaged by prolonged exposure to stomach acids. The condition is characterized by the abnormal growth of intestine-like cells called metaplasia, which can eventually lead to the development of a lethal form of cancer called esophageal adenocarcinoma. The precise origin of metaplasia in Barrett’s esophagus, however, has long been debated. An international team of researchers including Wa Xian from the A*STAR Institute of Medical Biology, Frank McKeon from the A*STAR Genome Institute of Singapore and Harvard University and Ho Khek Yu of the National University of Singapore has now tracked the origin of the precancerous growth to a previously overlooked group of embryonic cells.

The incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma has increased markedly in Western countries over the past few decades and has proved stubbornly difficult to treat at the advanced stage in which it is often detected, prompting researchers to look for an early detection protocol for this disease. As the gene p63 is known to be involved in the self-renewal of stem cells in the esophagus, Xian and McKeon’s research team turned to a p63 knockout mouse model to investigate the disease’s origins.

The research team showed that mutant mice lacking p63 develop Barrett’s metaplasia in a matter of days, with gene expression patterns nearly identical to those observed in the human condition. By tracing the expression of genes present in the metaplasia of the mutant mice and in Barrett’s esophagus throughout embryonic development, the researchers were able to show that the metaplasia originate from a small population of embryonic cells that persist at the junction between the esophagus and the stomach in both mice and humans (see image).

Mimicking tissue damage caused by stomach acids in humans, the researchers found that embryonic cells respond to the increased level of acidity by actively migrating away from the esophageal–stomach junction toward adjacent epithelial cells. The embryonic cells then compete with the damaged esophageal cells to occupy the basement membrane of the esophagus. Barrett’s metaplasia may develop as a result of this cell competition mechanism.

The new model raises the possibility of early treatments that could help to prevent the onset of esophageal cancer. “We are identifying new markers of Barrett’s metaplasia so that early treatment can be provided before the condition develops into cancer,” says Xian. The researchers are currently developing new therapies for Barrett’s esophagus as well as other precursors of stomach cancer.

The A*STAR-affiliated researchers contributing to this research are from the Institute of Medical Biology and the Genome Institute of Singapore.