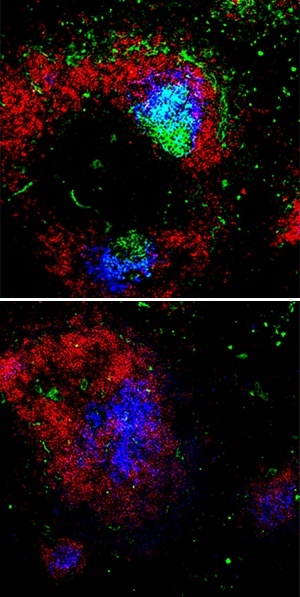

Germinal center (GC) B cells (green) are readily detectable together with dendritic cells (blue) in the spleens of wild-type mice (top) after immunization. However, in the absence of Dicer, B cells fail to accumulate within GCs (bottom).

During an infection, B cells in the bone marrow may undergo differentiation to become either plasma cells or memory cells. Plasma cells are responsible for producing antibodies for targeting pathogens, whereas memory cells ‘remember’ pathogens so they can respond quickly in subsequent encounters. The entire process of B-cell maturation — which includes the derivation of B cells from hematopoietic stem cells and the differentiation of B cells into proplasma and memory cells — is choreographed and regulated by various genes, proteins and enzymes. Most recently, scientists have learned that microRNA molecules, generated by the enzyme Dicer, contribute critically to the early stages of this maturation process.

Shengli Xu and co-workers at the A*STAR Bioprocessing Technology Institute and Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology have now evidenced that microRNAs are also essential to the final stages of B-cell maturation. “Previously we had no knowledge if Dicer — and hence microRNAs — are important for the optimal production of antibodies by B cells,” says Xu. “By selectively eliminating Dicer function in antigen-activated B cells, we now have proof that microRNAs play an important role in the differentiation of B cells into plasma cells.”

B cells are known to accumulate within structures known as germinal centers (GCs), where their interactions with dendritic and T cells induce a ’hypermutation’ of antibody genes that results in optimized recognition of infectious targets. In parallel, a process called ‘class switching’ yields diverse antibody subtypes. “Different antibody classes have specific functions, such as helping other immune cells to engulf microbial antigens or activating the complement system to destroy microbes,” explains Xu.

Both of these processes were seriously impaired in mice whose antigen-activated B cells lacked a functional Dicer gene, resulting in dramatically reduced antibody production in response to an immune challenge. These animals also exhibited considerably fewer B cells within GCs (see image), and failed to produce meaningful numbers of antibody-secreting plasma cells.

Since Dicer expression remained intact in precursor and naïve B cells, it was clear that these effects of microRNAs were specific to the activation process. Subsequent experiments identified numerous factors associated with cell proliferation and survival, in which levels were specifically dysregulated in Dicer-deficient B cells. These included Bim, a protein that triggers early cell death and is apparently normally repressed through the action of microRNAs in antigen-specific B cells.

Clarifying the specifics of microRNA involvement in B-cell proliferation and antibody production will be among the group’s next steps. “It would be interesting to see if Dicer is important for the generation of memory B cells,” adds Xu.

The A*STAR-affiliated researchers contributing to this research are from the Bioprocessing Technology Institute and the Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology.